Permutation no. 675

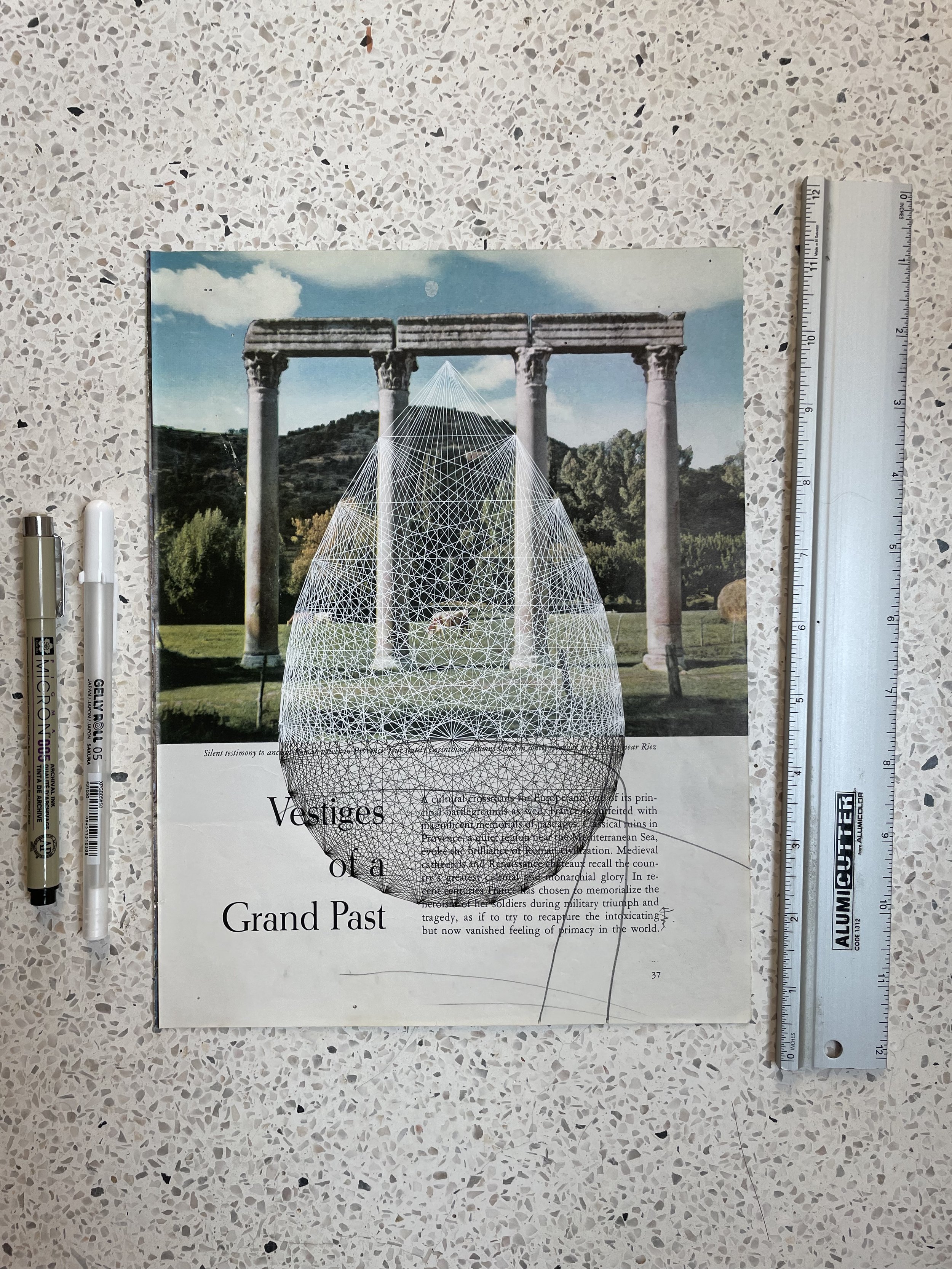

I was really drawn to the title of the chapter "Vestiges of a Grand Past." The image is of four Corinthian columns in Provence, France, erected during Roman occupation, back when France was still called Gaul, probably some time after year 0 A.D. I studied in Aix-en-Provence for a semester in college, but I don't think I ever made it to Riez, where this photo was taken. I have also been long-fascinated with ancient Roman history.

You'll notice that there are pencil scribbles on the page. When I first saw them, I thought maybe that disqualified it from being used, that the pencil marks somehow ruined the page.

But really, those pencil marks were most likely made by some young Indian student, no doubt wondering why they had to learn about the occupation of a people on another continent by an empire the book says evokes "the brilliance of Roman civilization" (colonizer empire lauding colonizer empire). This student was being taught in English, the language of the Empire who had only ceded their occupation 13 years before this book was published. Was this student's frustration about any of that, or just the typical "I hate school!" feeling we've all felt at some point in our academic lives?

I realize this is all quite a leap, but that's the magic of working with found materials. There is what the material says, what its intent was, the history and context that follows it, and then there is the intimate history of the material as an object, and the imagined life of its previous owners. It's why I think working with found materials is so special. Someone can try to go find this exact book and make a version of this piece, but they won’t be able to get tiny worms to eat it, or find the same young Indian student to scribble on it with a pencil.

Ink on Found Paper

8.5” x 10/75”

I was really drawn to the title of the chapter "Vestiges of a Grand Past." The image is of four Corinthian columns in Provence, France, erected during Roman occupation, back when France was still called Gaul, probably some time after year 0 A.D. I studied in Aix-en-Provence for a semester in college, but I don't think I ever made it to Riez, where this photo was taken. I have also been long-fascinated with ancient Roman history.

You'll notice that there are pencil scribbles on the page. When I first saw them, I thought maybe that disqualified it from being used, that the pencil marks somehow ruined the page.

But really, those pencil marks were most likely made by some young Indian student, no doubt wondering why they had to learn about the occupation of a people on another continent by an empire the book says evokes "the brilliance of Roman civilization" (colonizer empire lauding colonizer empire). This student was being taught in English, the language of the Empire who had only ceded their occupation 13 years before this book was published. Was this student's frustration about any of that, or just the typical "I hate school!" feeling we've all felt at some point in our academic lives?

I realize this is all quite a leap, but that's the magic of working with found materials. There is what the material says, what its intent was, the history and context that follows it, and then there is the intimate history of the material as an object, and the imagined life of its previous owners. It's why I think working with found materials is so special. Someone can try to go find this exact book and make a version of this piece, but they won’t be able to get tiny worms to eat it, or find the same young Indian student to scribble on it with a pencil.

Ink on Found Paper

8.5” x 10/75”

I was really drawn to the title of the chapter "Vestiges of a Grand Past." The image is of four Corinthian columns in Provence, France, erected during Roman occupation, back when France was still called Gaul, probably some time after year 0 A.D. I studied in Aix-en-Provence for a semester in college, but I don't think I ever made it to Riez, where this photo was taken. I have also been long-fascinated with ancient Roman history.

You'll notice that there are pencil scribbles on the page. When I first saw them, I thought maybe that disqualified it from being used, that the pencil marks somehow ruined the page.

But really, those pencil marks were most likely made by some young Indian student, no doubt wondering why they had to learn about the occupation of a people on another continent by an empire the book says evokes "the brilliance of Roman civilization" (colonizer empire lauding colonizer empire). This student was being taught in English, the language of the Empire who had only ceded their occupation 13 years before this book was published. Was this student's frustration about any of that, or just the typical "I hate school!" feeling we've all felt at some point in our academic lives?

I realize this is all quite a leap, but that's the magic of working with found materials. There is what the material says, what its intent was, the history and context that follows it, and then there is the intimate history of the material as an object, and the imagined life of its previous owners. It's why I think working with found materials is so special. Someone can try to go find this exact book and make a version of this piece, but they won’t be able to get tiny worms to eat it, or find the same young Indian student to scribble on it with a pencil.

Ink on Found Paper

8.5” x 10/75”